Providing vast expanses of green spaces help absorb the harmful carbon dioxide of the planet and pump oxygen

into the atmosphere. Therefore, countries have been working to increase their green areas for their beneficial

properties that help efforts to reduce global warming and climate change, and by default removing the threat to

societies and their environment. However, such greenery may sometimes be harmful or fatal, and a process that is

quite difficult to reverse, as it is costly for society and the state.

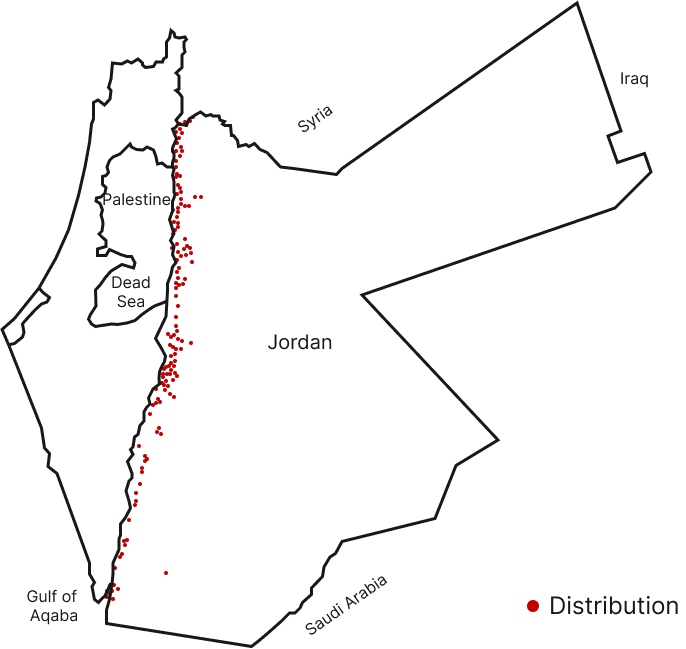

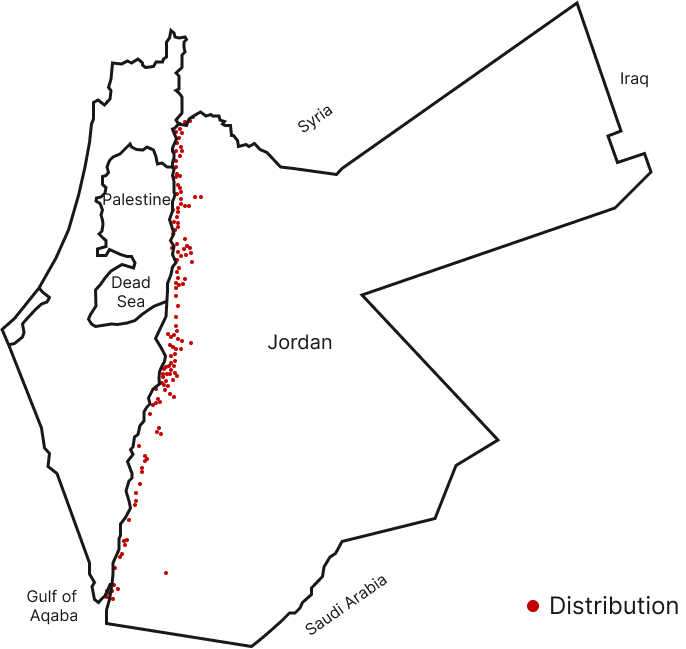

This investigation documents the story of the “Honey Mesquite tree”, which is among the ten worst species that

are alien to the ecosystem of Jordan, despite those trees’ overwhelming spread in the southern and northern

parts of the Jordan Valley, where they have impacted negatively people’s lives, farmers and their water

security.

Honey Mesquite trees spread and grow rapidly due to their ability to absorb surface and underground water as

deep as thirty metres, rendering some agricultural areas into barren lands.

The Prosopis juliflora tree, common name “honey mesquite”

The Prosopis juliflora tree, common name “honey mesquite”

The scientific name of the honey mesquite tree is Prosopis juliflora, Its journey across the world started from

its original habitat in Latin America, in countries like Venezuela and Colombia.

Natural distribution

Invasion

Cutting down trees

Studies have shown that the Ministry of Agriculture had introduced the Honey Mesquite tree to Jordan between

1950 and 1980, for afforestation and greening purposes, due to its characteristic ability to withstand diseases,

heat and water scarcity.

Hover over area to know more details

Hover over area to know more details

Sparse or non existent

homogenous

habitat

Invasive

Environmental experts later were alerted to the dangers of this tree. A study entitled “Prosopis (Prosopis

juliflora): Blessing and Bane” has revealed the impact of the spread of the Honey Mesquite tree in India. When

this tree is brought to a place other than its original habitat, it can become invasive because it overpowers

the native species and outdo them for resources. This type of trees is resilient and could withstand harsh

conditions, such as extreme temperatures, high salinity and poor soil conditions. It also hinders the growth of

other nearby plants as it spreads, monopolises space and blocks sunlight and nutrients from reaching other

plants.

This tree is considered an invasive specie in many countries.

The Black Book of Invasive Alien Plant Species of Jordan, (page 4)

prepared by GIZ and the National Centre for Agricultural Research, in cooperation with the Ministry of the

Environment classifies the tree among the top of the worst invasive species for the Jordanian environment.

Doctor Maher Tadros is a professor of plant production at the Jordan University of Science and Technology and has been involved in many studies related to the Honey Mesquite tree says that these trees destroy biodiversity, and local species cannot compete with them.

The biggest issue is that these trees have found the right conditions to spread particularly through the northern and southern part of the Jordan Valley areas in particular, doubling their negative impact on the agricultural sector as a whole, since this is the most significant agricultural area of Jordan providing the country with crops throughout the year.

Tadros says that some agricultural lands are no longer suitable for cultivation due to the spread of Honey Mesquite trees saying that, “in the past, farmers would plant tomatoes in some areas. When we asked, they said that this area has been taken over by honey mesquite trees.”

Wasted efforts

Wasted efforts

Ziyad, a farmer from the village of Al-Rama in the Dead Sea region has not been able to let his land for a

year because Honey Mesquite trees. He says, “Honey Mesquite trees have spread where there used to be banana

trees in my farmland. I need to use bulldozers to destroy the trees and reclaim the land. With the high cost

of diesel, renting a bulldozer for an hour costs 75 Dinars ($110), and then I have to pay for renting saws and

other special machines. None of these methods have managed to curb the spread of Honey Mesquite trees, on the

contrary, maybe they have contributed to their faster spread when water was available.”

A farmer has to follow a long list of procedures to be able to remove Honey Mesquite trees in order to reclaim

the land. A special request to cut the trees should be presented to the directorate of the Ministry of

Agriculture in the region where a committee from the agricultural directorates inspects the land for damages

and issues a license allowing the landowner to cut the trees causing the damage.

A study was conducted on an area of 11,800 square kilometres in the Afar region in Ethiopia, infested with

Money Mesquite trees, examined in depth the volume of water consumed by these trees, estimated that these

plants consume between 3.1 to 3.3 billion cubic metres of water, that is seven litres of water per tree.

To put these results in context, we have compared them with

the design capacity of all Jordanian dams. The reports issued by the Ministry of Water in 2020 revealed that

fourteen dams had a design capacity of 338.3 million cubic metres,

meaning that all Jordanian dams collect only about 10% of the water consumed by the Honey Mesquite trees. The

study was conducted on an area of approximately 13% of the total surface of Jordan, and its findings have

confirmed that there is a real problem if the issue has been left unresolved.

Anwar Al-Jaaraat, a farmer from the village of Sweimeh took us on a tour to see how the groundwater springs

have dried up after the spread of the Honey Mesquite trees in his region. He says, “The roots of the trees

extend over long distances under the ground, and they dried up most of the springs that people used to rely on

for cultivation in Sweimeh”.

According to Anwar, the five main springs of Ain Al-Ghourbeh, Al-Be’r El-Azraq, the Sweimeh Dam, Ain Al-Jame’e

and the well of the village area have all dried up, which led to a decline in agriculture as a result of the

water scarcity.

Jaafar attempted to mitigate the damage of the Honey Mesquite trees in his village by removing them, despite

the prohibition imposed by the Forestry Directorate in the Jordan Valley, “we used to cut the trees down

because they are harmful, but the Ministry of Agriculture had a problem with that, and would fine us with up

to 500 Dinars ($700) the first time, and the amount would increase if we cut them down again,” he says.

Article 18 of the Jordanian Forestry Law indicates that anyone who violates the provisions of any clause of

paragraphs (A, B) of Article (5) of the law shall be punished by imprisonment between one to three months, and

shall pay a fine between five to twenty-five Dinars for every tree, bush or sapling, or any part thereof.

Tools, forest plants shall be confiscated and sold for the benefit of the treasury.

Agriculture Law No. (13) of 2015 mandates the Ministry of Agriculture to oversee combating animal and plant

pests, epidemics, combating desertification; protecting biodiversity; and creating a suitable climate for

investment in the agricultural sector.

The Law issued by the Ministry of Agriculture

The Law issued by the Ministry of Agriculture

Click to view

the law

The head of the Forestry Directorate at the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture Engineer Khalid Al-Manasir has

confirmed that government nurseries have stopped producing Honey Mesquite saplings in recent years and did not

deny that nurseries still stocked them as those were the left over from previous years. Al-Manasir stressed

that these were precautionary measures awaiting the final classification of the Committee for Biodiversity

regarding this plant.

Click to view the documents

Documents showing that the production of Honey Mesquite saplings in government nurseries has stopped since 2020

Apart from the Jordan Valley, investment licenses have been issued to allow the cutting of forest trees throughout the year in private properties, and in some periods only in most regions excluding the Jordan Valley region.

Article (3) on the exclusion of the Jordan Valley area

Al-Manasir adds that getting rid of Honey Mesquite trees altogether has some legal implications as this tree

is considered a forest tree protected by regulations and laws that prevent the removal of all types of trees

as this constitutes a legal violation. Al- Manasir has pointed out that the committee is due to issue a

document confirming that this tree is invasive, and therefore strips it of its protective classification so it

can be removed.

The CEO of the Dead Sea Friends Association Zaid Al-Sawalqa says that the association has submitted an

investment project to the Ministry of Agriculture proposing the removal of Honey Mesquite trees and substitute

it by other local trees such as palm and Washingtonia instead. No response has been received from the Ministry

of Agriculture ahead of the publication of this investigation.

Engineer Bilal Quteishat, a delegate of the Ministry of Environment in the National Committee for

Biodiversity, says that the Honey Mesquite tree has an impact on biodiversity and on native plants like the

tamarix tree in the Dead Sea region. This, in turn, leads to the extinction of some animals like the Dead Sea

Sparrow that takes up the tamarix as its home.” He pointed out that the Honey Mesquite tree is not a good

environment for this bird, nor is it a habitat where it can build a nest.

When asked about the dangers the Honey Mesquite tree poses to the soil, Quteishat highlighted that in addition

to absorbing moisture from the soil, it breaks it up and changes its properties.

Engineer Bilal Quteishat explained that in order to remove the dangers posed by this type of trees, the

government nurseries should refrain from producing the Honey Mesquite trees, and cutting some down to conduct

some research to see how could we adapt to live with this tree in a way that benefits the ecosystem from its

strength and high levels of resistance.

Quteishat has discouraged from resorting to the use of chemicals to eradicate those trees, claiming that

traces of chemicals will persist in the soil long after the trees disappearance and could have an impact on

unground water. Therefore, removing them will have to be done biologically and in environmentally safe

methods.