In September each year, Quail and another 240 species of migratory birds take their annual journey from Europe to Africa, transiting in Egypt in search of warmth before returning home at the end of migration season. Unfortunately, the number of these birds is declining and they face the threat of extinction as they either end up as meals on Egyptian tables or hunted to be frozen for export.

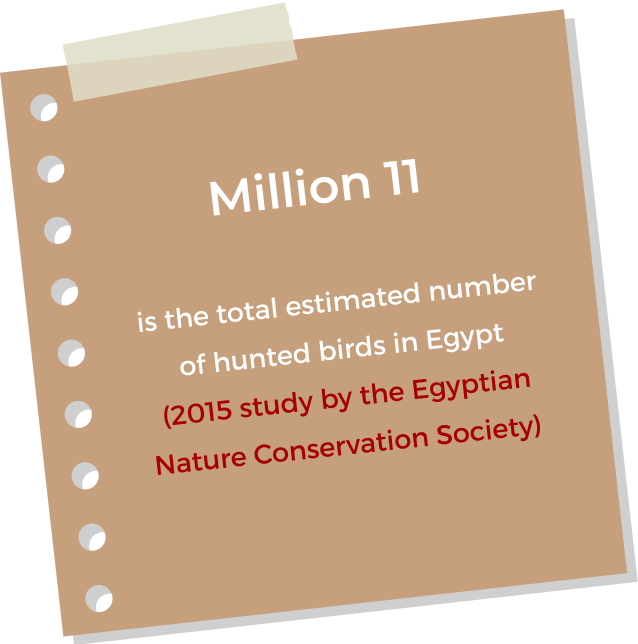

Egypt is considered to be the world’s second most important route for migratory birds, and despite its adherence to the international conventions for the protection of birds, the country’s lack of monitoring and inspection of hunting practices has led to an increase in the random and illegal hunting of migrating birds, threatening them with extinction.

Egypt is home to 34 important areas for birds migrating from Europe and Asia, including 15 declared as special nature reserves areas spread across 8 governorates, the most famous of which is the “Lake Burullus” reserve.

Inspection trip to hunting areas during migration season

This investigation took the reporters on a 200 km, three hour car ride from Cairo to Lake Burullus, to reach the first hunting site on the coast of Baltim overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. There, hunters set up several lines of trammel nets five meters high, in violation of Egypt’s National Hunting Regulations.

Bird hunting is a hobby that 60 year old Thabet Abu Zaid, inherited from his father. He owns a 1000 meter piece of coastal land where he has been setting up his hunting nets during migration seasons.

After receiving a seasonal hunting permit from the coast guards for 100 EGP ($5), Abu Zaid sets up his hunting net on an area not exceeding 200 meters. He says that most hunters do not adhere to the net size specified by the Ministry of Environment’s regulations which is published in the official newspaper on September 8, 2021.

The annual hunting decree, issued by the Ministry of Environment at the beginning of the hunting season in 2021, specifies the maximum area of coastal hunting nets not to exceed 200 meters (changed from 500 meters in 2001).

The ministry justifies the change by stating that, in certain regions, the previous larger net area would infringe on lakes or residential areas making it difficult for birds to find escape routes. It added that it is currently conducting a scientific study in collaboration with Egypt’s Nature Conservation Society, the national partner of the Birdlife International Organization, in order to determine the best size for hunting nets and regulate hunting practices according to scientific standards.

Illegal Sound Devices

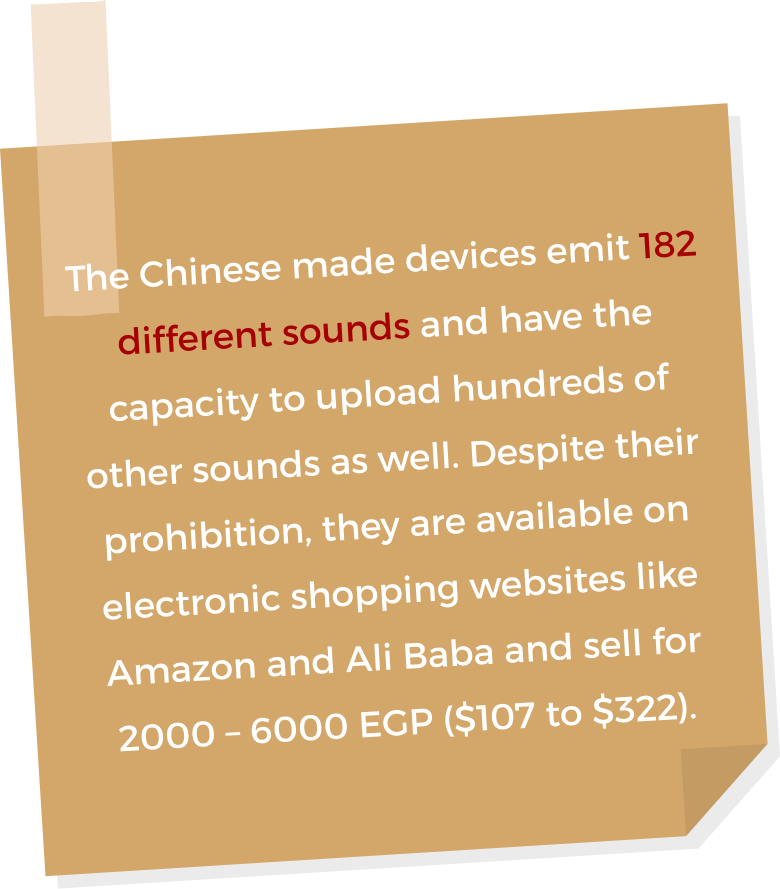

The Ministry of Environment’s annual hunting regulations decree prohibits the use of ultrasonic devices that attract quail and other bird species, conditional of denying those violators the necessary permit. We met a bird hunter and environmentalist who stated that using ultrasonic devices will ultimately contribute to the extinction of some bird species including quail.

These devices emit sounds that imitate the sound of migratory birds, attracting the birds to the sticky hunting nets set on trees, where they could remain trapped for hours and may even die before they get collected by the hunters. Each bird is then sold for about 10 EGP ($0.54 cents) to a merchant in the village of Mastarwa.

Our reporters headed to the village of Mastarwa, part of the Burullus region, 48 km from the Baltim coastline, in search of Shalaan (alias), a 30 year old hunter, who also works in the trade and maintenance of hunting sound devices.

Shalaan says he hunts 300 birds daily and his catches include quail, ducks, pintails, and greenfinch. He then offered to sell us a rare falcon the hunting of which has been prohibited by the Ministry of Environment. He added that this was not the first time he hunted falcons and that the last one was hunted in 2019 and sold for 267000 EGP ($14800) which was divided among 10 individuals who camped in the desert with their families for three months to try and catch one.

It’s hard to pass through the village of Mastarwa, without visiting the home of 60 year old Mohammad Falah, the self-proclaimed “prince of migratory birds,” who has been a bird hunter for the past 54 years and who describes himself as “the most important migratory bird merchant in Egypt.”

The front entrance to his house is lined with cages of chirping birds, and inside, a wall is adorned with pictures of him with the “Shaheen Falcons” he previously owned. Behind the wall is a room with large fridges full of hunted birds, in addition to a bathroom where they do the slaughtering, cleaning of those birds.

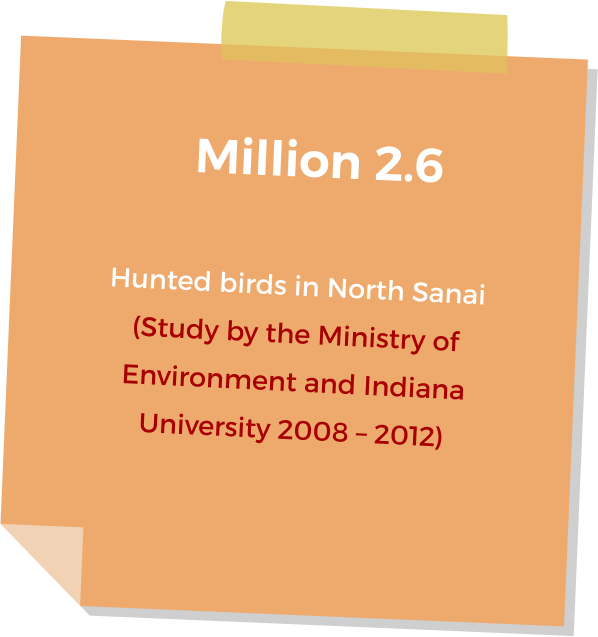

There has been a decline in the population of migratory quail in the North Sinai region as annually, 2.5 million birds are hunted around Lake Bardawil; a practice which will inevitably lead to the extinction of migratory quail, according to a study conducted by Omar Atom, Associate Professor of Biology at Indiana University in the United states.

The Ministry of Environment in Egypt allows the hunting of 21 species of migratory birds. Ayman Hamada, Head of the Central Department of Biodiversity in the ministry, states that there are two important criteria that are taken into account before granting hunting licenses, the first is the status of the species on the scale of endangerment as classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, while the second is the extent of sustainability for the global population of a particular species without risking extinction. He added that quails, so far, are not endangered and can be hunted safely within limits.

The Migratory Birds Business

According to a study conducted by the Ministry of Environment in Egypt, and in the Burullus nature reserve alone, some 1.416 million quails are caught during the three month hunting season, at a revenue of 5.6 million Egyptian Pounds ($285000). Sherif Baha’ Eddine, founder of Egypt’s Nature Conservation Society states that the booming business of exporting these birds to Arab Gulf countries is a driving force behind the fierce hunting business, adding that exporting began ten years ago through the systematic slaughter, packaging, and freezing of the hunted birds before export.

Egypt resumed the export of local birds and poultry in October 2020, in accordance with strict regulations on condition that those are farmed and not migratory. Law no. (4) of the year 1994 prohibits the import, export or selling of migratory birds either dead or alive, as a whole, in parts or their derivatives. Salwa Halawani, a researcher in Bird Life International says: “When birds are imported for consumption, it is hard to tell whether they are domestic and famed or migratory.”

A Heavenly Blessing

“Hunting migratory birds is what we do for a living. We have no other source of income. They are a blessing from God the Almighty.” Shalaan repeated this statement several times stressing that during hunting season, he heads out to the desert accompanied by his whole family to save on living expenses. He borrows the money he needs for his trip and pays it back upon his return after slaughtering and selling their hunted stock. Shalaan is no different to other hunters we met, for them “These birds are a heavenly blessings.”

Environmentalist researcher Salwa Halawani conducted a study on the socio-economic conditions of hunters, which angered the Ministry of Environment in Egypt as it has shed the light on the absence of the ministry’s monitoring of the practice, concluding that 75% of it is illegal. The study showed that most hunters make modest profits, except those who sell what they catch, adding that smaller songbirds sell for only 1 EGP ($.045) each, which means that the more birds caught the greater the profit, making the average daily income for a hunter around 500 EGP ($26).

Sherif Baha’ Eddine, founder of the Nature Conservation Society criticizes research institutes’ lack of interest in studying and monitoring hunting practices, stating that “the most important yet most difficult part of regulating the hunting sector, is possible only through improving the economic situation of hunters who rely heavily on the income from this practice.”

Baha’ Eddine’s suggested solution was applied to the Red Sea coastal city of Gebal El Zait, also known for its electricity generating wind farm complex. Saber Riyad, an environmental consultant and field supervisor of one of the area’s bird hunting projects, says that over the past five years, many of its residents have begun working with various entities and have received training on how to monitor the movement of birds and their routes, which created job opportunities with a higher return than the one earned from hunting migratory birds.

Ayman Hamada, Head of the Central Department of Biodiversity, referred to a socio-economic study on the living conditions of hunters conducted by the Ministry of Environment in cooperation with a project funded by the European Union and the French Facility for Global Environment, adding that the results of the study will soon be published by the ministry and aims to “find alternatives” for the socio-economic conditions and needs that drive hunters into this profession.

The Absence of Monitoring

Article 45 of the current Egyptian Constitution stipulates that the State shall commit to the protection of livestock and of all endangered species.

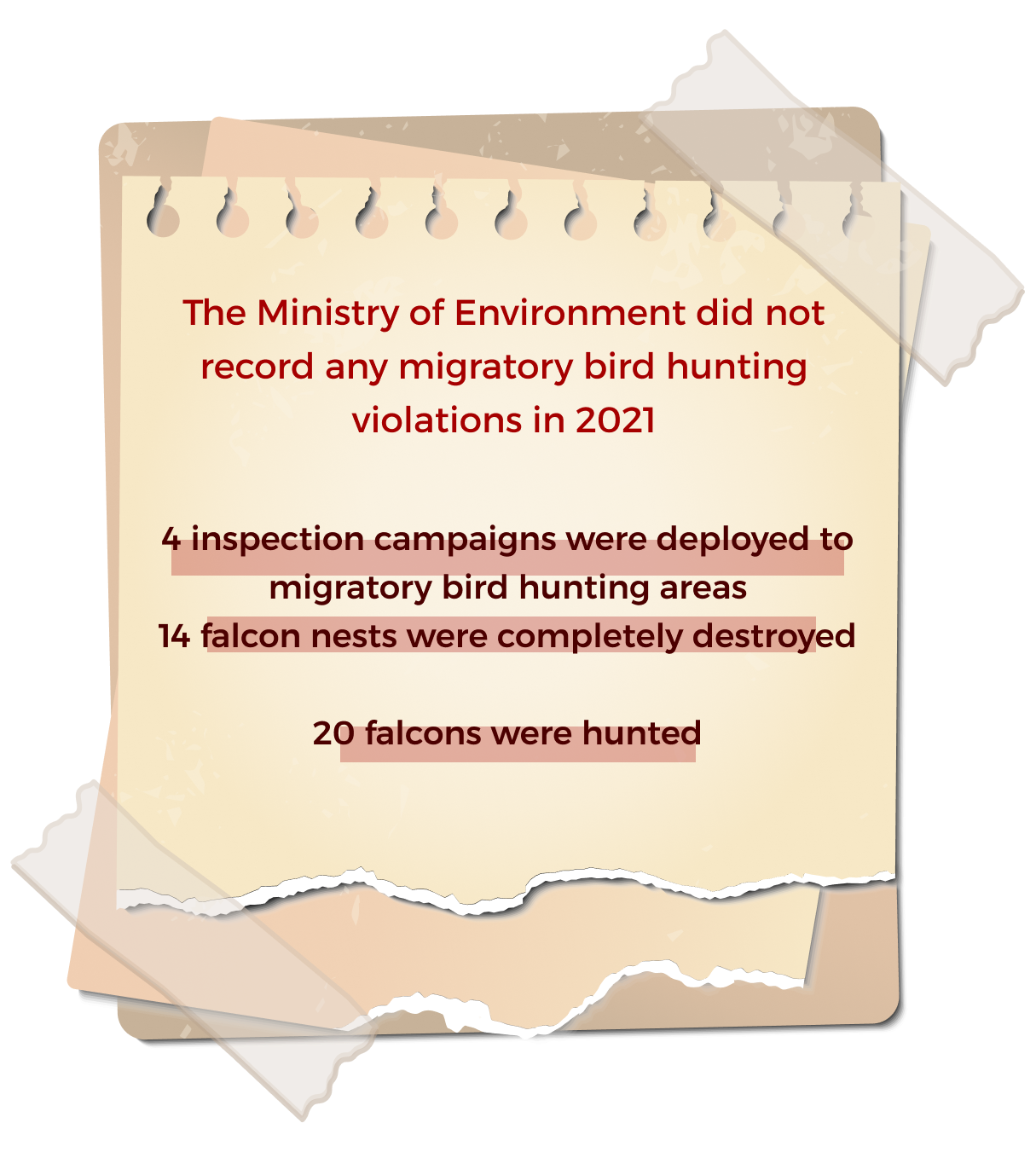

Mustafa Fouda, former biodiversity consultant in the Ministry of Environment, says that the government’s current efforts to monitor hunting practices are not enough and that there is weakness and complacency in the execution of the law. He added that adequate monitoring would require a multitude of resources in light of the current insufficient number of supervising staff members.

Fouda states that adequate monitoring relies first and foremost on the monitoring agents and their commitment to the enforcement of the law, adding that “monitoring agents would rather keep the status quo than risk losing their position.”

He also stated that monitoring is costly for the Ministry of Interior, which is responsible for providing a police force, for water and environmental emplacements, adding that despite some occasional “positive, individual efforts,” the state resources are often allocated for matters other than the protection of nature or migratory birds.

The former consultant also criticised the ministry’s issuance of an annual hunting regulations decree in the absence of a clear methodology for its execution, stressing that each year, many hunters hunt migratory birds without obtaining the proper licenses or permits. Violators should be subjected to the penalties stipulated in the amended law no. (9) of the year 2009, which raised the violation fine from 500 EGP to 30000 EGP ($1610).

Fouda states that the solution lies in the formation of an independent sector for the management of the state’s resources and nature reserves, and he even proposed a law he presented to Parliament and the government, for which he received no response. He reiterates the importance of a comprehensive legislation “that brings everything pertaining to nature under one roof, named the ‘Nature Conservation Authority,’ which would operate under the Ministry of Environment.”

The ministry admits its shortcomings with regards to the monitoring and enforcing hunting regulations and standards. Hamada states: “Our shortcomings are mainly due to limited resources, both human and financial, in addition to a lack of specialized vehicles that can reach and properly monitor hunting areas. We admit there is a problem in monitoring the implementation of legal hunting criteria, especially that the decline in bird populations, like quails, has become an issue hunters are aware of.”

Hamada says that the founding of an economic authority for the conservation of nature is a dream, as workers in this sector have been trying to achieve that since the late nineties. Some progress has been made and efforts may pick up again after the Climate Change Conference (COP 27), set to take place in Sharm El Sheikh in November, 2022. He added that turning this sector into a financially sustainable authority with its own economic resources will enable it to protect biodiversity more efficiently.

Bird Hunting Excursions

Migratory bird hunting may be viewed also as a “trade” for some, as we have found excursions advertised on Facebook for those interested in bird hunting as a ”hobby.” These trips are not promoted under “eco-tourism,” and include the use of multi shot rifles, in order to hunt a larger number of birds. These weapons are illegal and are often used in the Northern Coast of Egypt, from Alamain to Salloum.

We have contacted a migratory bird hunting excursions organiser in Fayyoum named Abu Ahmad, who says that “hunting migratory birds in Lake Qarun is illegal, which is why we have created artificial lakes or ponds to attract the birds’ gathering.”

Article 15 of Egypt’s Law for the Protection and Development of Lakes and Fisheries no. (146) of 2021, prohibits the exploitation, building of facilities, businesses or practices on lands within lake regions, unless licensed by the state.

Hamada adds that “We have problems with ligation procedures, as hunters avoid legal prosecution by claiming that their online accounts were hacked or that pictures have been fabricated, or they were able to flee by the time environmental police forces reach their reported locations.”

Migratory Birds and Climate Changes

Egypt has signed many international conventions pertaining to the protection of endangered migratory bird species, the most important of which are the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) and the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds especially falcons and the Egyptian eagles.

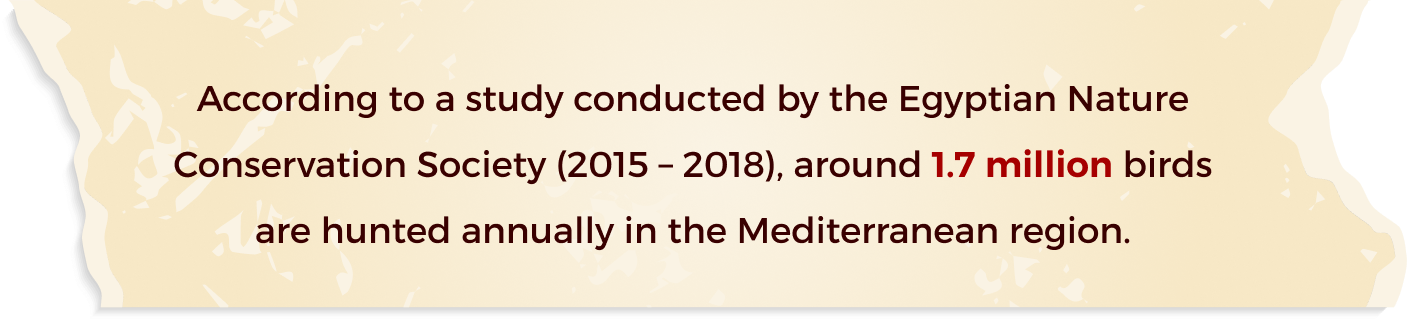

However, hunting is not the only factor destroying natural bird habitats. There is also the problem of climate change. Baha’ Eddine states that the annual monitoring and recording of migratory bird routes has shown a change in both bird species and numbers. Some have increased, others decreased while new species have also been recorded.

He adds that wetlands and lakes such as Lake Manzala and Lake Burullus have been affected by a decrease in volume and even the Northern Coast has turned into an urban rather than coastal environment. All these factors affect local bird species more than migratory ones.

Khaled Al Nubi , the Executive Director of Egypt’s Nature Conservation Society, currently working on a PhD thesis on migratory bird species and how they are affected by climate change confirms that the dwindling number of species and migratory birds have been affected by global warming and the decrease in water resources which endangers their role in preserving biodiversity.

The new migratory bird hunting season is quickly approaching amidst the continuous lack of regulatory measures and their fragmentation among various government entities that render them ineffective in preventing the erosion of the stocks of migratory birds population, especially quails, thus raising the possibility of facing an autumn without quail.