Eight months after the end of her prison sentence, Olfat Saeed, 21, exits the prison gates in a body bag, a casualty of the bombing of the Central Women’s Prison in the city of Taiz, Yemen, on 5 April 2020. The attack killed six women prisoners and two children, one of them born in prison and the other visiting his incarcerated mother.

Note:

Photos Copyright @ Yemeni Photographer Khaled Al Qadi

Note:

Photos Copyright @ Yemeni Photographer Khaled Al Qadi

Saeed had done her time. She died because she was one among dozens of Yemeni women prisoners who have been denied release from prison after serving their sentences. The reasons vary from request of their own families, driven by social pressure, to the absence of a male family member to whom they could be released, to illegal policies implemented by prison authorities under the pretext of protecting these women from possible violence upon release.

Amina Ahmad, 22, was also an inmate in the Taiz Women’s Prison when the Houthi rebels attacked it. She had also remained incarcerated after completing her prison sentence - in her case, for five months. More fortunately than Saeed, however, she survived the attack and today lives in a women’s shelter.

“I was imprisoned for a crime I did not commit. My family disowned and abandoned me. I was one of the casualties of the horrific terrible bombing of the prison,” Ahmad says, “The ugliness of what we witnessed instilled in me a fear that has made me unable to deal with people or talk to anyone.”

Two days after the attack, the inmates were transferred to the same women’s shelter. Ahmad says that things are better now and that the shelter’s supervisor is a kind mother figure.

Amina recalls a fellow inmate who died during the attack. “She was imprisoned for no reason other than the fact that her father wanted to punish her for being disobedient. She remained in prison indefinitely with no contact by family members and when she died in the attack, her family refused to receive her body.”

The Yemeni government, however, denies that stories like these are true. It says that in areas under its control, which include Taiz, no woman is imprisoned beyond her sentence.

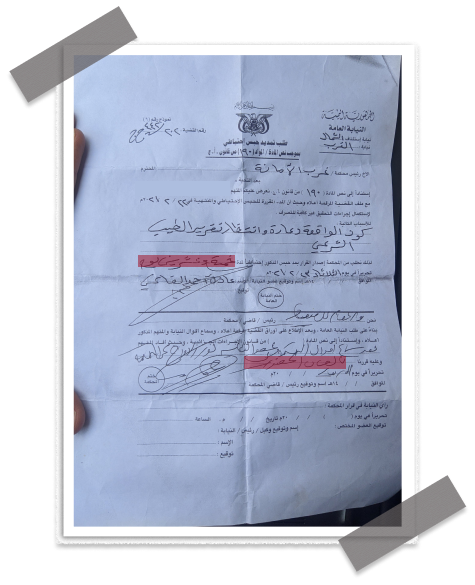

The situation is no better in the parts of Yemen that the Houthiscontrol, such as the country’s capital, Sanaa’. There, underage girls are also subjected to indefinite incarceration. Shama al Arhabi, 14, has been detained in Sanaa’s Central Prison since 22 February. Al Arhabi, who sold tissues and water bottles on the streets of Sanaa’, was in prison because she had refused a gangster’s attempt to extort money from her. As revenge, the gangster accused her of ‘immoral behavior’ with the result thatshe was arrested and detained despite committing no crime, according to lawyer and activist Naseem Al Mahthali, who is also a member of the Yemen Women Union.

الشرط

الشرط

الإفراج بالضمان الحضوري

مدة التجديد

مدة التجديد

25 يوم

The attorney general ordered her release due to the lack of evidence, but Judge Essam Meyad renewed her detention, says Al Mahthali.

The authorities will not free her unless a male family member is present to accompany her when she is released. But this is impossible for Al Arhabi: her father is dead and she has no brothers or relatives besides the paternal aunt with whom she lived.

Her continued imprisonment breaks Yemen’s Juvenile Law, which stipulates that the detention of juveniles, when necessary, should be in social welfare centers, - not prison.

Other laws, too, should make it impossible to deprive women of their freedom after they have served a prison sentence. The Yemeni Penal Code does not include any provisions that would allow this to happen. It also does not require the presence of a male guardian for their release. On the contrary, the law makes it a criminal offence to detain inmates after serving their sentences. The Yemeni constitution stipulates that “The state shall guarantee to its citizens their personal freedom, preserve their dignity and their security. The law shall define the cases in which citizens’ freedom may be restricted. Personal freedom cannot be restricted without the decision of a competent court of law.”

So, theoretically, the detention of any person after the end of their sentence violates Yemeni law. But in reality, incarcerated women are treated in accordance to some kind of unwritten ‘customary’ law. The absence of special provisions for women prisoners in official law causes loopholes that allow the application of these customs all across the divided country.

Abdul Rahman Al Zabib, a legal consultant for Maysarah for Development, a national Institute advocating for the rights of prisoners, says that these loopholes are a result of “the overhasty enactment of the law after the Yemeni Unification on 22 May 1990, without taking into account the nature of the Yemeni society and its traditions, hence producing a law that tyrannizes women inmates.”

According to Al Zabib, the continued detention of women after serving the prison sentences determined by the courts or prosecutors is a violation of human rights agreements and declarations, in addition to the rights of inmates guaranteed by the Yemeni Constitution.

He adds: “Whoever enacted the law should have considered the lack of gender equality in Yemeni society and, therefore, should have included provisions specific to women inmates rather than referring to inmates in general.”

“The continued detention of women inmates on the pretext of the absence of family members or guarantees is a form of violence based on gender”, says Al Zabib.

Lawyer Raghda Al Maqtari says that it is a crime, adding that “no provisions in the constitution, law, or prison regulations condone such illegal practices which have become customary in women prisons for some time. One cannot deny the negative psychological effects on the inmates, in addition to traumatic events like the recent bombing of the prison.”

Lawyer Naseem Al Mahthali took over the case of inmate Yusra, 21, who remained incarcerated one year after the end of her original court-ordered sentence. Yusra, according to her lawyer, was a victim of rape whose perpetrator got away unpunished. “She suffers from epilepsy attacks that leave her unconscious. One day while she was grazing her family’s herd of sheep in the rural area of Ibb [under Houthi control], when she had a sudden epilepsy attack and was raped by someone while she was unconscious, only to discover, five months later, that she was pregnant.”

At the time of the attack, Yusra lived with her parents and a step-mother with a son from a previous marriage. Initially Yusra accused him of the rape before recanting and accusing the ‘sheikh’ of their area. All her accusations were merely speculations since she did not know who had actually raped her while unconscious. According to her lawyer, Yusra says that her father tried to kill her after finding out about the pregnancy, so she fled her home seeking protection with a Houthi officer. She was referred to the General Prosecutor in Ibb for adultery and later to the central women’s prison in Sanaa’, according to Al Mahthali.

Al Mahthali tried to obtain an order from the prosecutor allowing Yusra to serve her sentence outside of prison, until she delivers her baby. However, the prosecutor insisted on handing Yusra over to a family member only, which was a problem since her family had disowned and abandoned her.

The ‘sheikh’ she accused of rape had threatened to kill her if she was ever released. But instead of providing her with a safe release and protection, as she requested through her lawyer, Yusra was forced to give birth in prison. An order for her release was later issued after she received a flogging sentence of 100 lashes. Yet Yusra and her baby girl remain in prison one year on, according to her lawyer. “The baby gets sick almost every week and rarely receives treatment, while her mother cries continuously in fear of losing her infant any minute.”

Al Zabib says that the continued detention of children with their incarcerated mothers is a crime against childhood.

Suha Al Aryani, an activist and legal consultant with the National Prisoner Foundation in Sanaa’, says that the problem of children in prison extends to the refusal of their family members to take any form of responsibility for the child’s care or welfare.

“One inmate had two daughters who remained with her in prison for eight years. Another inmate in Ibb delivered her baby in prison, and at the age of eight, her daughter and another child were removed from prison into the custody of the National Prisoner Foundation.”

Twelve inmates live together in the women’s shelter and rehabilitation center in Taiz, sharing food, rooms and sometimes even clothes. The center tries to be an ‘alternative family’ for the women who were abandoned by their families after finishing their prison sentences. Ahmad, like others, was fortunate twice; first, by surviving the bombing attack, and second, by finding a safe shelter instead of spending the rest of her life behind prison walls.

Shadia Rajeh, head of the shelter and rehab center, is sympathetic towards the women in her residence and tries to compensate for the lack of family support in their lives, stating: “Before the shelter was established, I used to pay regular visits to the prison to follow up on inmate cases, and noticed that there were orders of release for several women who were not allowed to leave because their families had abandoned them. This is how the idea for a women’s shelter was born, especially after the attack on their prison which killed several inmates who had already served their sentences.”

In order to free an inmate and enroll her in the rehabilitation center, Rajeh had to first get a licence from the Ministry of Social Affairs to verify that her centre's activities are legal. Only then can she coordinate with the prison’s management and the prosecutor to get each woman released. She says she rarely faces any obstacles from the prison’s management or prosecutor because “it is within their interest that these inmates are released after serving their sentences instead of becoming a burden on the prison, and the existence of rehab centers keeps them safe from dangers they may face on the street.”

The officials, specialists and even the victims interviewed during this investigation, both in government and Houthi controlled areas, all agreed that a large proportion of the dilemma facing women inmates in Yemen was due to a lack of shelters that could provide a safe alternative living environment after their release, and prevent authorities from extending their detention on the pretext of absent family members.

According to Suha Aryani, there are not enough alternative detention centers where women who have not been convicted of a crime can stay during the various stages of investigation. These centers would provide protection from the stigma of serving time in a prison which remains associated with these women even after being proven innocent.

She adds that “the current number of shelters can accommodate a limited number of residents, as is the case with the two shelters in Sanaa’, one for abused women and the other for underage girls. Therefore, some inmates are forced to remain in detention as the long processes of courts and prosecutors drag on. It is also worth mentioning that most of these women are declared innocent of the crimes that led to their incarceration.” However, their families still refuse to take them back, due to the mere fact that they served time in prison.

According to official statistics (until March, 2020), 376 women are incarcerated across Yemen.[22] 57 inmates have completed their sentences yet are still being detained. 17 of these are held in what is known as “liberated areas” controlled by the Yemeni government, while the other 40 are held in areas controlled by the Ansar Allah group or the Houthis.

Anas Saif, the Deputy Director of the prison authority in Yemen’s internationally recognized government, denies the detention of any women inmates beyond their legal sentences in any area under the control of the government, stating: “This issue was resolved in 2019 and 2020. One of the measures taken to contain the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic was to release all inmates, men and women, who had served their prison sentences. We also established a women’s shelter in Adan, hence the issue of released women inmates was thoroughly resolved.”

In areas controlled by the Houthis, authorities are more strict at prohibiting the release of women inmates without the personal presence of a male family member, despite the fact that no legal provisions stipulate such a practice. Colonel Mohammad Abali, Deputy Director of the prison authority in Sanaa’ justifies that by saying that, “the reality of our society forces us into this practice. We cannot simply throw women out on the street. There used to be a women’s shelter in the past but it was closed due to the scarcity of resources.”

However, a source who prefers to remain anonymous said that, in early December of 2019, the UNDP presented the governments of Sanaa’ (the Houthis) and Adan (the Yemeni government) with a proposal to train and rehabilitate women inmates and establish women’s shelters to accommodate them after the end of their sentences.

The Houthis, for unknown reasons, rejected the proposal, while the Yemeni government welcomed it and provided all needed capabilities and facilities for its successful implementation in the areas under their control. Still, women inmates in remote areas all across the country, inaccessible to organizations of human rights and civil society, remain behind bars even after serving their sentences.

Al Abali acknowledged that men are released, without hindrance, at the end of their sentences while women inmates, in contrast, are kept in detention in “out of fear for them,” especially in special rights cases like fraud and embezzlement, because, he adds, “if we present an insolvency petition to the Zakat (Charity) Commission, it will refuse to pay the required sums of money, on the pretext that such types of cases do not qualify to receive zakat funds, even if the inmate spends ten years in prison.”

It’s different for men, according to Al Zabib. Insolvency aid often finds its way to male prisons, he says: “We always hear of male inmates being released on the basis of insolvency, but never a woman inmate, which is clearly a form of discrimination.

Al Dailami, Deputy Minister of Human Rights in the Houthi government goes as far as saying that, “The problem does not merely lie in the fact that these women are detained beyond their sentences, but rather in the fact that, for social reasons, they would either be killed or work in prostitution because they are now ‘damaged goods’ in society.”

This form of discrimination has negative psychological effects on women inmates, says Shadia Rajeh, head of the women’s shelter and rehabilitation center in Taiz, who examined a group of released women. She adds: “When an inmate is released, she is referred to a psychologist who determines if she needs medication or counselling.”

According to Abdul Rahman Al Zabib, what adds psychological damage is that all sorts of women prisoners are detained together. “An inmate who is a criminal gangster is held with someone detained due to a personal or a simpler issue. This takes a mental toll on the long and short run.”

As long as authorities continue to ignore the law under the pretext of custom or protection, and family abandonment persists, girls like Shama Al Arhabi and others will remain under illegal detention and will spend their lives deprived of both real protection and hope of any near release from prison.